A bright red seaplane swoops low over a bay, as sailors waive up to the goggled pilot above in this unique and historic painting of early aviation over water.

The year was 1919, and the world had just emerged from the darkness of World War I. The skies were filled with the promise of new beginnings, and the thrill of aviation was sweeping the globe. In this era of daring aviators and cutting-edge aircraft, one event would capture the imagination of the world like no other– the Schneider Trophy Race. It would become the world’s most prestigious aviation prize with nations vying for air supremacy over its courses.

The race was established in 1913 by Jacques Schneider, a wealthy Frenchman with a passion for aviation. Schneider’s wealth allowed him exposure to aviation pioneers such as the Wright Brothers and to other wealthy patrons offering prizes to the best aircraft. One of these was J. Gordon Bennett, a name which should be familiar to our readers as the publisher of the New York Herald and as a famed American yachtsman, Commodore of the NYYC, and owner of HENRIETTA from the Great Transatlantic Yacht Race.

It was at the banquet following the fourth Gordon Bennett Aviation Cup race for landplanes at Chicago in 1912, that Schneider announced La Coupe d’Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, and 75,000 francs to the winner. It would be an annual competition to encourage the development of practical aircraft capable of operating reliably from the open sea with a good payload and reasonable range. He was clear this was not to be just a contest of speed. He also decreed that the competition would be wound up when one country won his trophy three times in a row.

But why seaplanes? Schneider believed that, since most of the world’s major cities were built on coasts or major rivers, float planes would dominate aviation as it moved into civilian and commercial use. The trophy itself was a work of art, a silver seaplane perched atop a massive marble base, a symbol of the race’s challenge and grandeur.

Bournemouth was selected as the venue for the 1919 Schneider Trophy race, marking a significant return after the First World War. The decision was influenced by the region’s rich history of aviation interest, and Bournemouth’s crucial role as a center for training of pilots for the new Royal Flying Corps in WWI.

Leading up to the race, teams from three countries underwent trials. British racers, along with French and Italian teams, prepared at various locations. The race, organized by the Royal Aero Club, was set to cover ten timed laps of 20 nautical miles over a triangular course that ran west from Bournemouth Pier to Durlston Head, returning across Poole Bay to Hengistbury Head and back to the finish line at Boscombe Pier.

On race day, thick sea-fog initially hampered visibility, but as large crowds gathered, it receded with the tide, prompting officials to proceed. The weather didn’t last- the fog returned and all of the British and French racers were forced to abandon the course, leaving only Italy’s Guido Janello in his Savoia S.13 flying boat.

Janello not only finished the race, he did it in a time faster than his plane’s known top speed, only to discover he had been disqualified for failing to fully complete the Swanage turn in the fog, rounding a reserve boat instead of the official marker. The pilot claimed he had been poorly sighted and accused officials of cheating him. Outraged that the race was declared a no contest, the Italians were only partially pacified by being awarded the honor of staging the next race. If the Italian plane had been awarded the victory it would have been the third in a row, and the cup would have gone permanently to Italy.

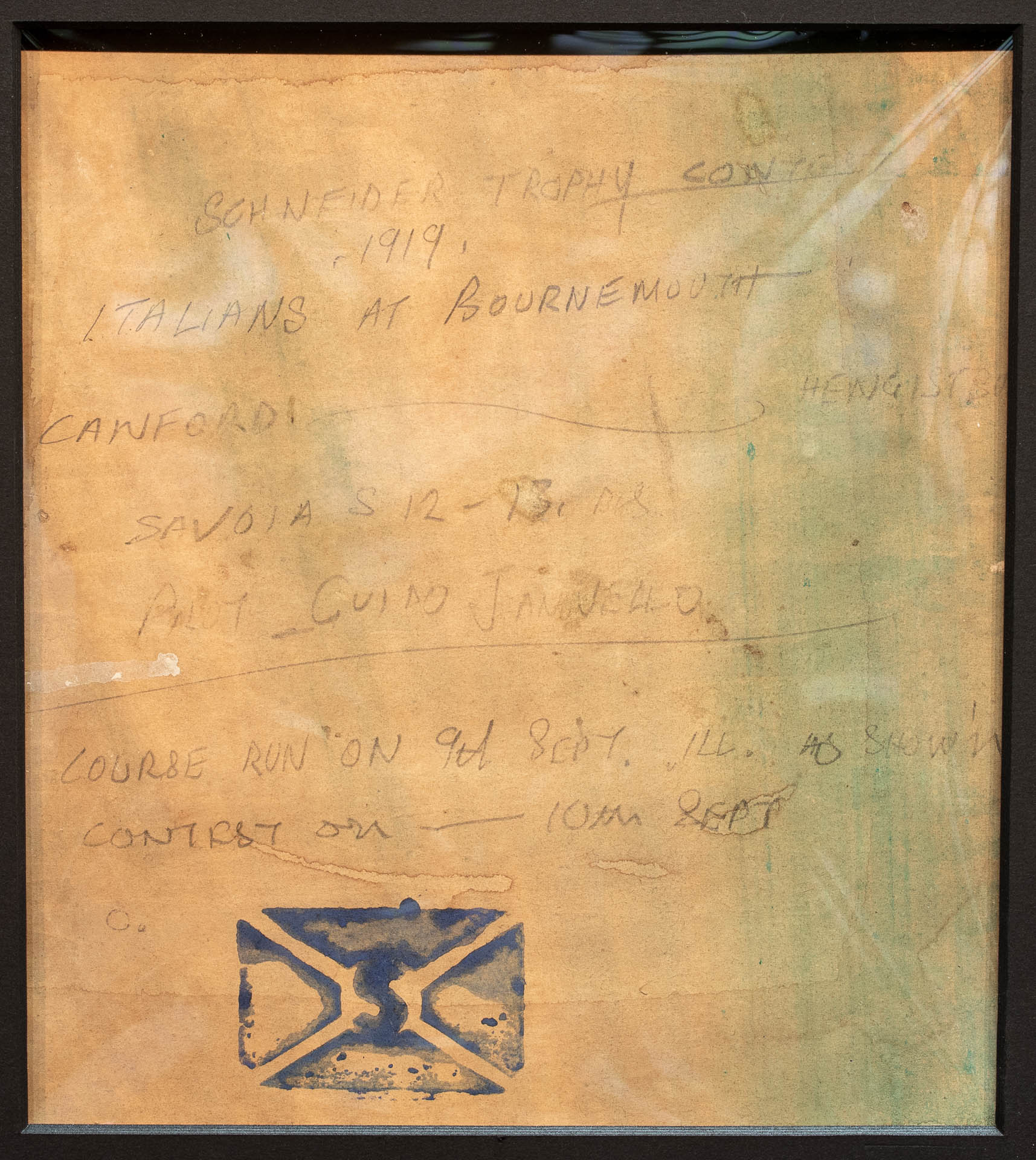

This painting captures the thrill and hope of flight and of the daring of its early pioneers. The plane is featured brilliantly, with its shining Italian flag painted on its tail. The propeller spins as the wings catch the air currents; the pilot seems composed and intent on his task. The painting is inscribed with details of the plane and event not only on its face but also verso which we have had framed with a window to display. Period early aviation art is rare, as is a painting of such an important event.

The race was held 12 times in all, from 1912 to 1931 with Britain eventually winning the cup permanently. The contests were extremely popular, with some races attracting over 200,000 spectators. The race was important in advancing aircraft design, especially in the field of aerodynamics and engine design, and its results would be reflected in the best fighter aircraft of World War II. The streamlined shapes and low-drag liquid-cooled engines pioneered by the Schneider Trophy design are evident in the British Supermarine Spitfire, the American North American P-51 Mustang and the Italian Macchi C.202 Folgole.

Today, the Schneider Trophy resides in perpetuity in London’s Science Museum and Bournemouth’s part in its history is commemorated by a storyboard at Spyglass Point.

Painting Inscribed LR: S.12-13 Course Run, Bournemouth 1919. The painting is signed with initials but we’ve been unable to match it to a known artist.

The back of the painting is inscribed in pencil: Schnieder Trophy Contest, 1919. The Italians at Bournemouth. Canford——– Hengistbury, Savoia S12-13, Pilot Guido Janello. Course Run on 9th Sept., ill. as shown. Contest on 10th Sept.